On National Handloom Day, let’s expand the narrative beyond weavers, to include farmers, spinners, dyers, and all those who constitute the larger handloom narrative ecosystem

National Handloom Day is the right moment to realign the narrative—to include not just weavers but farmers, spinners, dyers, and all those who constitute the larger ecosystem of Indian handlooms.

There has been a significant shift in India’s handloom discourse in recent years. Increased investment in R&D, efforts towards digital inclusion, and a growing data-driven framework for connectivity among handloom workers. Government promotions now position textiles and handlooms as vibrant aspects of India’s cultural identity. Even lifestyle and fashion media, with its inherent glamour, has begun to report more seriously on these issues.

Yet, each year on National Handloom Day, media stories largely circle back to the weaver—their struggles, artistry, and resilience—while other key links in the value chain remain underrepresented. Cotton and jute farmers, silk rearers, fibre-makers, spinners, and dyers—along with those who wash, reel, roll, and colour the yarn—remain in the shadows. They make the weaver’s work possible. Why are they still missing from the frame?

This year, The Voice of Fashion brings you a special issue that begins with Eri silk or Ryndia, often referred to as Ahimsa silk. We chose this fibre as a symbolic but complex entry point because its production challenges easy narratives. The farmer-rearer-spinner-dyer-weaver chain of Ryndia sustains entire communities in Meghalaya and parts of the Northeast. Using this as an underrepresented metaphor, we explore deeper questions around value, labour, language, technology, and the environment.

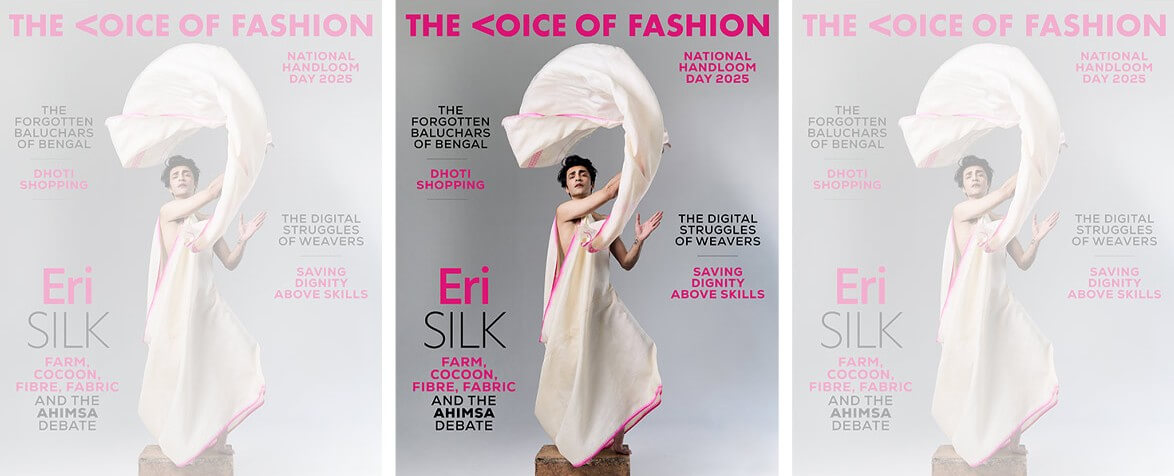

Every aspect of this edition has been woven together with intention. On our cover is singer-songwriter Prashantt Verma in a silken Phee-Phanek, a Manipuri garment from 11 Tareng, woven on the loin loom. The cover shoot—styled by fashion and design writer Varun Rana and photographed by our house photographer Rishabh Batra—features drapes from Bengal and the Northeast.

Each of our in-house writers have contributed to this issue. Anannya Sarkar speaks to Ally Matthan of the Registry of Sarees on the question: what do we really save when we say we are saving handlooms? Unnati Saini interviews Verma, who transitioned from fashion design to music. Kimi Dangor journeys into the forgotten Baluchars of Bengal, in conversation with Darshan Shah of Kolkata’s Weavers Studio.

To deepen this dialogue, we invited outside voices with distinct perspectives. Osama Manzar, co-founder of Digital Empowerment Foundation, writes about how technology now discriminates against handloom workers who remain labelled as labourers rather than technologists or artisan-engineers. Dastkar’s Laila Tyabji critiques what the fashion industry continues to misunderstand about handlooms. And Caimera founder Kirti Poonia, who also set up Okhai, highlights the ongoing struggles of handloom workers trying to sell online.

My own reporting focuses on Eri silk. With inputs from designers based in Assam and Meghalaya, grassroots activists and innovators, and conversations with the principal secretary of the Meghalaya government, we return to the often-ignored significance of the silk cocoon rearer. In exploring the label “Ahimsa,” we also pose a cultural contradiction—since the cocoon is consumed as food in parts of Meghalaya, can we still call it non-violent?

The broader intent across these nuanced narratives is to shift the lens from the end handloom products such as the sari, the dupatta, or the cloth, to the processes and people that sustain it. Because the logic of capitalism, with its focus on product and profit, risks rendering these links invisible.

I hope you enjoy the photographs, the writing, and the rigour behind each of these stories. Handloom is on a high—and its momentum is contagious.