From farm to fabric, Eri silk resists fashion’s urge to convert it into a “trend.’ Ryndia is a silk, but more than that it is about community, a cultural practice, and a rhythm of rural life in Meghalaya

On Independence Day next week, among those invited to the President’s traditional “At Home” reception at Rashtrapati Bhavan are farmers who grow soy and mustard under the National Mission on Edible Oilseeds. Their inclusion hints at the country’s push for self-reliance in edible oils. It’s also a reminder of who gets visibility—both visual and notional—in national celebrations, and who does not.

Cotton farmers won’t be there. Nor will those who rear wool or cultivate Eri cocoons for Ryndia silk. The labour of the Ryndia farmer is intergenerational, rooted in community and local. Its value lies more in cultural continuity than commercial success, especially outside the Northeast. It seldom finds space in the national imagination—unless it is dressed in the marketing language of Ahimsa (non-violent) silk. A contested label, it nonetheless helps government campaigns frame Meghalaya’s indigenous fibre through a Gandhian lens, albeit retrofitted.

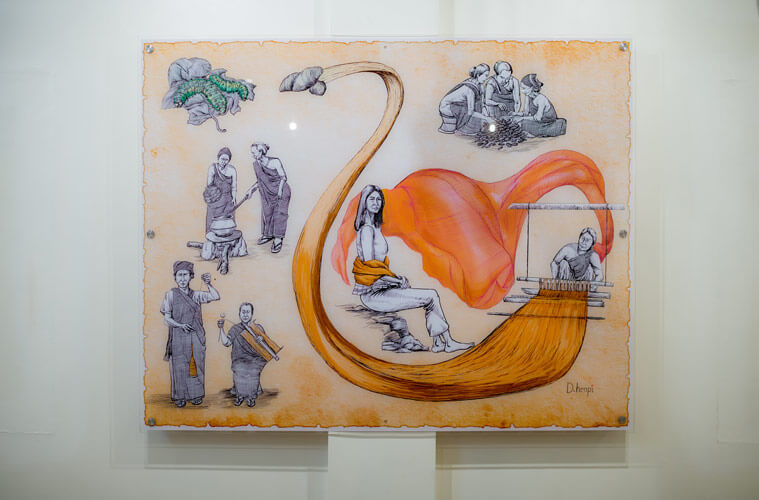

But Eri silk—or Ryndia, as it is called in Meghalaya—is not a symbolic fabric. Grown, spun, woven with some of its silk worms eaten by the Bhoi community, it is not a product of industry, nor just khadi in philosophy. It is a living practice. As India celebrates its handloom heritage this August, Ryndia offers a question: can a textile be celebrated for its value chain without being pulled into the pressure of becoming a trend?

The Forgotten Links

Craft and social design facilitator Juhi Pandey—former head of the Centre for Excellence in Khadi (CoEK) in Meghalaya—warned this writer against romanticising only the “handloom” end of the process for National Handloom Day. “Handloom is one of the final stages before a rural, hand-created product becomes commercial,” she said, speaking from Jaipur, where she has since relocated.

With past experience at Khamir in Kutch, Pandey learned that what sets handloom apart from mill-made cloth are the overlooked stages: farming, rearing, spinning, reeling, dyeing.

During her time at CoEK, Pandey identified Eri as a fibre of regional identity—prevalent across Meghalaya and Assam, and used in Nagaland and Arunachal Pradesh (where it is not reared) in various drapes and forms. But its production remained fragmented, she felt. “Even though cocoon production is high in Meghalaya, there’s no Khadi centre there,” she explained. “So, traders would take the yarn to Assam to get it spun. That’s where designers and weavers usually source it from.”

As India marks National Handloom Day with hundreds of images of weavers at their looms—backs bent, fingers flying, some smiling, others briefly remembered, the story of Ryndia remains largely unacknowledged. And more so its uniqueness, complexity, and difficulty with simplification or trend-sparking.

Ryndia and the GI Tag: A Living Textile with a Nameplate

Earlier this year, Ryndia silk and Khasi handloom received Geographical Indication (GI) status. “Uniquely, this entire value chain—from farm to fibre to fabric to fashion—is organic,” says Frederick Roy Kharkongor, Principal Secretary, Government of Meghalaya. Based in Shillong, he believes Eri silk is more relevant than ever amid environmental concerns.

Kharkongor referenced government campaigns where the Ryndia logo is now visible across departmental platforms, and even Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s mention of Ryndia in his monthly Mann Ki Baat address. He shared images of Meghalaya’s Silk Village, and the many farmers who are also spinners.

“It is not just a value chain. It is a life cycle,” says Kharkongor. “Rooted in tribal ethos, in the co-existence of man and nature—a powerful idea in the face of climate change.”

As Ryndia is pitched to fashion designers (Kharkongor cited a visit to Meghalaya by designer duo Falguni Shane Peacock), he emphasised the importance of dyers. “More than 36 natural dyes are used to enhance the palette versatility of Eri. It’s like cooking a dish—each ingredient matters. The weaver may finish the piece, but the raw material defines its quality.”

Ryndia is, then, a sustainability story embedded in community practice. As environmentalists will argue and textile conservationists may agree, preserving the fibre means little without preserving the people who carry its memory and practice it almost religiously.

When a Cocoon Feeds and Weaves

In markets across Assam and Meghalaya, Eri cocoons are sold as food. In the farms that they are reared they are also spun into yarn on drop-spindle looms—ingenious, indigenous tools. On a Khadi exploration trip to Meghalaya, guided by Pandey, this writer saw the yarn from the cocoon being woven. It was a realisation that what feeds some, clothes others.

“It’s not easy to rear Eri,” says Dipti Nair, a former consultant with the Meghalaya State Rural Livelihoods Society (MSRLS), now based in Ri-Bhoi district. “The worms feed on tapioca or castor leaves, which must be replaced twice a day.” She is currently focusing on refining Eri silk yarn using traditional and modern approaches for designing textiles and has spun Eri herself.

Reares, she says, sort cocoons carefully. The pupa from the cocoons is mostly for food but some of the cocoons are allowed to grow into moths to produce eggs. “Often, the same person is the farmer, spinner, and trader—and it takes a month to produce just one kilo of yarn.”

Nair describes Ryndia as an ecosystem of labour. Poor infrastructure—transport, electricity, disconnection from outside consultants—adds to the strain. “Spinners as well as weavers face injury. Their mental and physical bandwidth is often not factored when infrastructure doesn’t support their process,” she says. While spindle-spun yarn is durable, machine-spun Eri breaks easily. Solar-powered spinning with silk is an option but it is work in progress.

And then there’s the material itself. “Eri silk doesn’t feel Mulberry which is the propagated and commercial idea of silk. It is not silken,” she says. “We’re still weaving it the way it was 100 years ago and we need to push it beyond traditional understanding.”

The labour of the Ryndia farmer is intergenerational, rooted in community and local.

Community Over Commerce

It has been 15 years since Meghalaya-based designer Daniel Syiem began to work closely with Ryndia. A sericulture officer introduced him to weavers, inviting him to meet farmers, spinners and other parts of the value chain, setting him on a path away from his work at a nightclub to becoming a designer. He was the first to take Eri to fashion shows abroad, and among the earliest to use it in garments, reinterpreting the traditional Khasi Jainsem in Ryndia. “Its use in Jainsems is recent,” he says. “Before that, Eri was mostly used for shawls and stoles.” His connection to the fibre is, in his words, “spiritual.”

This sentiment resonates with Iba Mallai, founder of Kiniho, a fashion-forward, sustainable label rooted in Eri. She doesn’t use the word, but her references are almost reverential. “When I returned to Meghalaya urged by my mother, I couldn’t imagine working with anything else,” she says. “Eri helped me reconnect with my community, where rearing cocoons and spinning yarn are part of everyday life.”

Kiniho’s collections now include Jainsems, shawls, dresses, and men’s shirts. In our conversation Malai rarely uses the word “fashion.” Her language centres on family, continuity, and cultural rootedness.

Syiem says that Meghalaya’s Eri weaving community has grown, aided by government grants. “Mostly women weave. Often, the same family farms cocoons, spools yarn, spins and weaves. But to me, the spinner is key,” he says. “People expect uniformity in texture or colour. But this isn’t a machine-made product. That’s not the point. It’s a niche market, and I wouldn’t want to mass produce it.”

The Ahimsa Debate

Eri silk isn’t boiled like mulberry, which is why it’s often labelled Ahimsa or non-violent silk. But nearly everyone interviewed for this story—except Kharkongor—disagrees with the label. Designers, artists, grassroots workers, and researchers see it as a convenient projection, shaped more by climate virtue signalling than ground realities.

“Many in the Bhoi community consume the worms—it’s part of our culture in the Northeast,” says Malai. “During past famines, it was a vital source of nutrition.”

Jagrity Phukan, artist and designer, the founder of Way of Living Design Studio in Assam, is more direct: “It’s the capitalist way. People pay for campaigns and beautiful stories and it needs a branding language.”

She describes the full cycle of Eri rearing—the worms eating castor or keseru leaves, making cocoons inside dried banana and mango leaves, tying them in old cloth, tending to cocoons in home gardens. The fascination when the moth becomes a butterfly. “Yes, for silk, yarn is taken after the moth leaves the cocoon. But cocoons used for food must be cut,” she says. “Farmers can sell edible cocoons for ₹1200–₹1600 a kilo, while yarn cocoons fetch ₹800–₹1000. That’s an economic choice.”

The government’s Ahimsa label, then, flattens out a layered reality—that silk is not just a fabric, but food, income, and culture.

Ryndia, By Hand and Heart

Phukan, who works with 24 spinners (mostly for Muga), is now developing an Eri-focused collection—stoles, mufflers, yardage, and zero-waste products made from loom scraps. “I saw my mother spin silk. The finest yarn is always the most beautiful,” she says. “Even what the worms are fed influences the texture.”

As the reporting for this story drew to a close, Meghalaya’s Silk Village, came up as a more honest branding exercise given the debate around the Ahimsa pitch, which could get called out for its conflicts. Pandey believes that with better systems and structure, Eri could become Meghalaya’s defining identity without competing with Bengal’s cotton.

But should Ryndia even scale?

This silk—matte, textured, and without sheen—isn’t a commodity in Meghalaya. It’s a life practice. Turning it into trendy fashion or making garments out of it risks missing its essence.

Perhaps Ryndia is best left as it is: limited-edition, handmade, hand spun, and handwoven. A fibre for which the farmer, spinner, dyer, and weaver can take an intergenerational bow—not for campaigns, but for continuity itself.