New York mayor-elect Zohran Mamdani’s wife Rama Duwaji stands intriguingly askew in style, part art-school, part diasporic mix-and-match. She eschews political performance, yet uses appearance as identity. Should we care?

“Rama isn’t just my wife. She’s an incredible artist, who deserves to be known on her own terms,” said New York’s mayor-elect Zohran Mamdani, way back in May. Then, as he cheered at his recent win—his 28-year-old Gen Z wife, illustrator and animator Rama Duwaji, by his side—he called her hayati. My life.

The remarks were both an announcement and a reminder—perhaps to himself as much as to the public—about the risk his wife now runs in his shadow. With every appearance, she could be prey to the voyeurism built around political wives, her looks decoded to fit two narratives. One that is partly theirs as a Muslim couple, one of Indian origin and the other Syrian, and partly the one we, the spectators, can’t resist pasting onto them.

The Sanctimonious Age of Looking

Ready-made narratives and style dissections of politicians’ wives (not husbands, let’s note) are real dangers. We live in a sanctimoniously dangerous age of appearance commentary. Sanctimonious because it runs a double script—one that claims to rise above surface obsessions even as it feeds on them. Instagram, still addicted to its own reflection, insists on being charmed by itself even as its power as a convincing media pit is on the wane.

Fashion, meanwhile, is choking on its contradictions. Pollution and microplastic-heavy, yet endlessly moralising through “content” that still circles the Kardashians, anti-ageing serums, and the latest Ozempic-chiselled ideal. Gen Z was supposed to be our escape gate from the formulaic fashion hell where age, size, and privilege bully talent, inventiveness, and resistance. Instead, the generation-as-metaphor seems to be lugging its own formula.

It rolls out as something like this: “We don’t like brands, we don’t like logos, we don’t follow the Kardashians, we don’t care for Botox, Instagram filters, religion, or power rooted in patriarchy. We care about sustainability, boxy fits, algae-green nail polish, and protests.”

It sounds refreshing, until you check the ground reality. We’re still waiting for Gen Z leaders to shift the needle in fashion, civil society, and climate politics (Greta Thunberg and her tribe aside). What the world is waking up to is that Gen Z, too, carries baggage, a certain hollowness around anti-aesthetics. They’re not old enough to shed it, but it is heavy enough to trip on.

The Wife as Mirror

With that as the background hum, what does Rama Duwaji’s decolonised diaspora woman—Syrian-American, at least in looks—do for us? Are we learning to care about who she is, or merely following the formula: applaud a political leader’s wife because she happens to be filmmaker Mira Nair’s daughter-in-law?

Mamdani’s insistence on his wife’s artist identity has reason. She is interested in sketching and ceramics, in animation as art and art as an animated expression in a world where rage is right, and listening is an art. Her Vogue US illustrations of garment workers in New York suggest she knows the inequities of fashion. The clothes she wears are easy to love because she looks ravishing in ways that outlast them. Youthful, self-aware, other-aware.

But if we were to systematically break down her look, at least in what she turned up in for Mamdani’s victory party—a top with Tatreez embroidery from Palestine by designer Zeid Hijazi, a skirt from NY designer Ulla Johnson, (later or before some Bhavya Ramesh jewellery from India)—she is clearly fitting out a formula. Her identity, consciousness of clothes as political and in “designer” fashion. Hijazi is a Palestinian designer from England. Her gold hoops and “love-with-Zohran” smile beguile, but she didn’t exactly arrive in art-school thrift. She cupped her hands into a heart and sketched New York City, somewhat predictable, somewhat charmingly off-beat.

As the next first lady of New York City, she faces a tougher stage. Her sketches tell us about her views on humanitarian causes and injustices from Sudan to Gaza. She spent years in Dubai and is informed of the Middle East’s political complexities. But the spotlight is already shaping her definition: “Black Riding Good” in her repeat black boots, a symbol before she’s written her own script.

Which is why it’s hard to swallow a line from a recent New York Times article that quotes a photographer calling her a “modern-day Princess Diana”. Hopefully not. Among Diana’s tragedies was being reduced to her reflection—a fashion diva with a collapsing core. That’s the danger Duwaji, and by extension Mamdani, must now wrestle with.

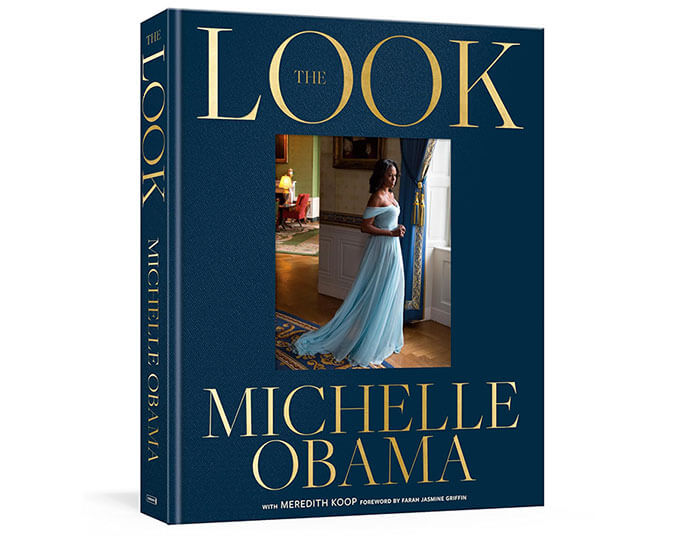

Learning from Michelle

Former FLOTUS Michelle Obama’s new book The Look breaks down the scrutiny over her appearance during the eight years the Obamas spent in the White House. “Others were trying to write our story before we could write it ourselves. So, I was like, let me not create another distraction: let me focus this country on getting to understand me as the First Lady through my work and my actions,” she writes.

That may be the line Duwaji could hold. Because the question is not just what she wears, but why we’re watching before we’ve begun listening.