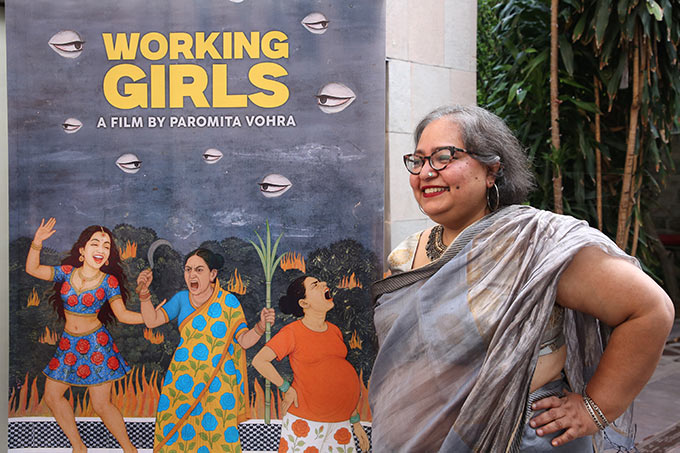

On a travel circuit with her latest documentary Working Girls, set to screen in Mumbai tomorrow, filmmaker Paromita Vohra talks about the interplay between feminism and autonomy and the rose as a central symbol to her way of thinking

“Anyone who watches Working Girls will feel slapped. They will feel attacked. Some will feel attacked for one reason and others for something else,” a team member told writer-filmmaker Paromita Vohra while they were editing the documentary. “About time, right? It is not about making us comfortable,” responded Vohra—Parodevi to many, after the name of her company, Parodevi Pictures.

She recalls that exchange as she cuts into the granite of the complex grammar of relating for this interview—of paid and unpaid labour by women, their conditional acceptance and sometimes their daily neglect, whether they are seen as individuals or merely registered as wombs and bodies that care, serve, subsist.

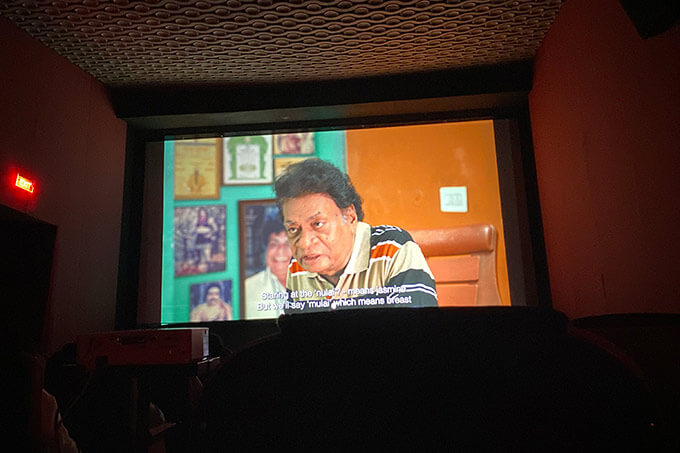

First screened in Delhi this July, Working Girls was played last evening in Bangkok, will be shown tomorrow in Mumbai, followed by Bangalore next week and will continue travelling through February. Shot across India, the documentary zooms into the invisible labour performed by domestic workers, sex workers, bar dancers, ASHA workers, reproductive surrogacy and farmers. It also discourses about unpaid labour by women at home in their own homes.

Working Girls is part of The Laws of Social Reproduction, a project at the Dickson Poon School of Law, King’s College London, conceived by professor Prabha Kotiswaran.

As Vohra speaks on our video call—sharing some ideas tender, others trenchant, quite like her work of 30 years—she peels the “rose” petal by petal, talking about what the flower means to her. A fragrance emerges: reflective, vulnerable, and uninterested in reducing complexity to something quote-worthy. Addressing audiences that are culturally diverse on panels and speaker pits, in the language of reason, rebellion and rights, with signature rose in hair—she comes across as someone for whom optimism is practice and discipline. The wry irony and smart humour in her writing is seeded in this optimism. She rejects fatigue. She carries the weight of what she witnesses, but by naming that weight, she finds ways to lift it. The rose blooms, but never without thorns.

Here, she talks about the poetic politics of her feminism and the reactions of her “working girls” when they first watched the film. Edited excerpts:

Why did you call this film Working Girls?

Because with “working girls” the implication is that there is a woman who works and a woman who does not. The term is not a question only of what you are, but who you are. It carries a sense of freedom, autonomy, confidence. There is an individuality in it, which I think is very light-hearted. The idea is of a career girl who thinks about life in a broader way. I wanted to evoke that.

More than 20 years back, I made a film called Unlimited Girls, so there is also a journey from Unlimited Girls to Working Girls (Hey, office-going madam, shift a bit, like you, I am also a working girl…). Recently, when I was in Trivandrum to show the film to ASHA workers, whom I had filmed with, they felt they had been recognised as “not just” contributing to society.

Also, the word “girl” is often used to infantilise women. But the term ‘working girl’, in my mind, has a little bit of glamour to it. There is a line at the end of the film from a song we made which goes, “Office wali madam zara khisak udhar, tere maafik mein bhi hu ek working girl…” Everybody was so happy with that line. That was my desire to bring different types of women in one context.

How do you define yourself? Who is Paromita Vohra today?

That’s tough. I think I am an artist. And I think I am a working girl. Work has been not only a defining factor but the pathway to friendship, self-awareness, expressing myself. And I am a feminist.

There is a part of life which is prosaic, functional. There’s also a part which is poetic, being a certain kind of person in relationship to others. This is every human being’s central dilemma. To trust your intuition and walk down a certain path, you need something that helps you think it through. For me, the idea of feminism and the idea of art are the same.

What does the rose mean to you? You wear a flower all the time.

The idea of the rose is central to my thinking, to the symbolism I’m interested in. It has many petals. It’s a prismatic object. You’re able to see the world in a way and there is no one way. That’s how I think of myself. My politics is a poetic politics.

Was there anything in the making of the film that stayed with you like a little bit of a weight?

When Prabha Kotiswaran invited me to make the film, I said yes right away. A lot of my work has centred around urban experiences. Especially with feminism, which has become very limited to online discourse. Many people who think of themselves as feminists have very little relationship with women. The idea of class needs to enter the discourse much more deeply.

This was an opportunity to explore those things. Working Girls is also a film about marriage—being a mother, having sex, keeping house. These are divine labours and have to be done to keep society going. The moment women do those jobs outside marriage, they become stigmatised. It really shows you that marriage is structured in a certain way to maintain gender and caste as it is.

I knew going in it would be tough because I would be entering the lives of people… who are very tough. What’s my right to even do that? How should I engage with that space? These were big questions. I don’t believe that just because you’re making a documentary, you’re making any difference in the world.

What stayed with me were things like being invited to have dinner with the women. When it was time for me to leave, they were missing something, as they were being really seen. These small moments stayed with me. For instance, the ASHA workers in Trivandrum sitting on strike for nine months—I feel that sense of impossibility.

You have not displaced men in Working Girls… no one comes out as memorable but they are all there.

Among the things that I have learned through my website Agents of Ishq is that politics should be about the things you believe in and love and not what you hate. I am not a person who spends my time critiquing the patriarchy, because I’m not interested in the patriarchy.

Women are not only symbols of feminism. They are just themselves—their work, their life. The men are also just men. They are also poor, have their gender biases and poverty. Very often men are not represented as people in relationships with others. It is possible to look at people that way, knowing they carry the weight of patriarchy or casteism. You can accommodate both truths.

Over this long experience of 30 years do you see real change in women on the ground?

A certain autonomy, yes. From 1995 to now, it is a sea change. The way women are articulating themselves is very different; they are able to see themselves as more than upholders of tradition. They are willing to take some risks.

I was struck by older women wanting to wear pants, while younger women came along in saris. For older women, dressing up is to wear pants—it is freedom. When they came to pick me up or drop me, they were in pants and shirts, just as lawyers wear. A striking image. The whole time they were driving me, there was so much complaining about men, frank conversations about sexuality. I could not have had these conversations 20 years ago as a stranger.

Some who had seen the film came up to me and said, “My heart is so touched, I am proud of you.” The Hindi word samanta describes this kind of exchange the best—that we are on the same plane. These are shifts of how women from different classes have become more confident. They have had to work because there is no choice but it gives them a sense of freedom and self-knowledge about their strengths and capability.