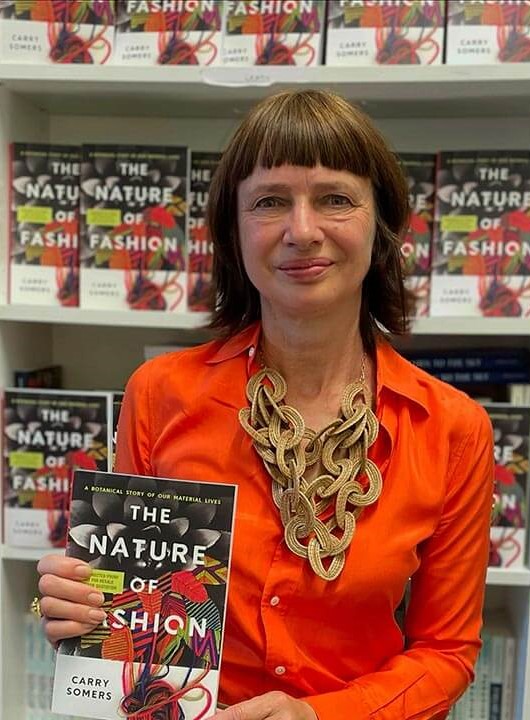

In her new book ‘The Nature of Fashion’, Carry Somers traces cloth from Ice Age string to industrial-era effluent, showing how fibres record humanity’s choices—good and catastrophic. An interview on history and hope

“A tapestry of sciences from anthropology to archaeology, botany to biology, carpology to climate change—The Nature of Fashion is more than an understanding of sustainable fashion practices. It is a guidebook that postulates how fabric strung our history together and how it is directing our species’ future.” Those are the words of Dr Gabby Wild, National Geographic author, wildlife veterinarian and conservationist, describing Carry Somers’ new book.

They convey the sentiment and the information without which it is hard to describe the gravitas of Somers’ work. The co-founder of Fashion Revolution, the world’s largest fashion activism platform, and the founder of Pachacuti, a Fair Trade-certified company, which has done pioneering work in supply chain transparency, Somers offers a fascinating tapestry that links nature, fashion, threads, fibres, dyes, colours and personal histories. What emerges in this negotiation through colossal losses leading to ecological degradation and dissonance between our clothes, their origin stories and us, is optimism. “Ours is an incredibly powerful generation, and the weight of responsibility can feel overwhelming. But with power comes agency, and the chance to act decisively,” she says. Her central argument—that “material progress and ecological loss have long been entwined, a pattern humankind keeps repeating”—is both an insight and a caution. What draws the reader is the interconnectedness of what our ancestors chose and how we mirror memory and inheritance through material history. Edited excerpts from an email interview.

Why do you think material history is such an important tool to draw attention to ecological degradation and climate change?

Material history allows us to see that ecological degradation isn’t just a modern problem. It’s a pattern. That’s why the narrative arc in The Nature of Fashion stretches from the Ice Age to the present day. When you follow fibres across time, from the earliest twist of string made by Neanderthals, to dyed flax in Dzudzuana cave, to the felling of brazilwood trees along the Atlantic coast, you can see how the choices people make alter cultures and landscapes. Sometimes catastrophically. Every fibre is a record of cause and effect. Telling this material history is a way of making climate change and biodiversity loss tangible: it places the evidence directly in our hands in a way that facts and figures alone never could.

Ultimately, tracing the story of people and plants over millennia—when we got it wrong and when we got it right—helps us imagine a future that breaks from the logic that created this mess in the first place. It shows that the world has been otherwise before, and can be once again.

Did the book’s research from “exploitation to idealism” across centuries, leave you a psychologically and philosophically burdened person?

I set out to write a hopeful book, always trying to draw something positive from each story, but it’s impossible to ignore the long shadow of exploitation and erasure, particularly during the era of colonial extraction. What particularly struck me was how often the same patterns resurface: the privatisation of shared commons, the pursuit of profit at the expense of ecosystems. This is what happens when we build a worldview that treats nature as something outside ourselves—interchangeable raw inputs rather than a living system. Fashion absorbed that same logic, turning plants into commodities, stripped of their relationships.

But the research clarified what is at stake and strengthened my belief in our ability to change, as we have throughout human history. The stories I uncovered are a reminder that history isn’t linear. It is created by people who make choices, who protect what they love, who imagine a different future, even through difficult times.

I mostly wrote the book in a small caravan overlooking the sea in Devon, in the south-west of England, and kept returning to the image of the local red-sailed Beer Luggers. In centuries past, with skill and sensitivity to the shifting winds, these small, agile boats could easily outmanoeuvre a bigger ship. For me, these small boats are a metaphor for the times we are living through. There are infinite unwritten futures to choose from. All it takes is the courage to set our sails and steer into the unknown, trusting the world will reshape itself as we go.

Through the lens of Pachacuti, your company which works on supply chain transparency and Fair Trade, can you tell us where, in your informed understanding, does India stand on these issues?

Pachacuti has always worked in Latin America, so I don’t claim any authority on India’s artisan economy. However, through my work at Fashion Revolution, my research for The Nature of Fashion, and more recently through researching and authoring the CRAFTED Report and the Artisans’ Index, I’ve gained a deeper understanding of India’s position in the global textiles system.

It seems to me that in India these two truths sit side by side. On one hand, there is an extraordinary depth of craft knowledge, a continuation of traditions that stretch back centuries, if not millennia. On the other hand, the country has endured devastating extraction, from violent oppression during colonial indigo cultivation to the industrial pollution that affects workshop clusters today.

I agree that narratives are too often muddled. The idea that craft is intrinsically sustainable because it is handmade is simply misleading. I’ve seen too many artisans emptying their dyes into local rivers to believe this. And these days, many raw materials used by artisans are sourced and dyed through industrial processes. What the CRAFTED Report made clear is that the challenges faced by artisans are mostly about power imbalances: insecure payment systems, brands drawing on traditional designs without credit, consent or recompense, and environmental pressures including toxic effluent, water stress and dangerously-high levels of air pollution. These threaten both ecosystems and the crafts rooted in them, because the threads of cultural survival and ecological preservation are not separate; they are like warp and weft, strengthening one another. The task now is to align policy, brands and investors to carry these traditions forward.

Given your work in investigating microplastic pollution, how did it inform, alert and caution you as a consumer?

My research into microplastic pollution reshaped how I think about fibres. On a scientific research voyage from the Galapagos to Easter Island, the ocean looked pristine, but when we dropped our sampling apparatus and sifted the water, it was full of small plastic particles and fibres. But it was the sediment cores from Rudyard Lake, just beyond my front gate, that shifted all my assumptions.

Sediment at the bottom of lakes acts like a time machine, revealing changes in fibres and pollutants over the years. Our analysis found cotton was the most common fibre type, present throughout the core, with wool in the older layers. Some of those fibres had been sitting in the lake for 140 years, since the final years of the Industrial Revolution. In fact, now we have started to look for natural fibres instead of dissolving them to isolate the plastics, we find they comprise upwards of 70 per cent of fibres in most sample environments.

Once natural fibres pass through chemical processes and treatments, including synthetic dyes, their behaviour changes. These days, natural is no guarantee of biodegradability and that realisation influenced my choices. We need to think not simply what fibres we are buying, but how they were grown, coloured, treated.

For readers, I’d say that the first step isn’t to buy differently but to see differently; to understand that every fibre has a landscape behind it. If we lose sight of that, materials become abstract and disposable. When we recover that awareness, our choices will shift almost automatically. Wearing what we already own for longer or buying second-hand is important, not only to reduce the strain on virgin resources, but because the first wash is the greatest when it comes to fibre shed. And in every twist of every thread lies the possibility of getting it right once again.