This year’s winner of the National Award for Design Excellence on the abundance of choice for Indian designers working with textiles, and the boat-bridge between innovation and invigorating storytelling

Through the glass windows of the new Vriksh store at Delhi’s luxury mall The Kunj, Gunjan Jain appears with her back turned, quietly rearranging hangers that hold Ikat jackets and sari drapes. The space is a study in contrast, restraint offset by a burst of bright—one wall lime green, the others a shade of ivory. The saris in the window speak before she does: a Rothko-like silk in deep brown, its pallu dissolving into immersive colour fields. And, her award-winning interpretation of the Navgunjara motif, which represents Vishnu’s vishwarupa or universal form, rendered on silk in azure and red. The mythical form is refracted into nine-fold imagination on the pallu, with a resplendent border that uses yellow thread making it look like gold.

Gunjan turns, dressed in a black salwar-kameez, a beaded ochre-and-cinnamon necklace from Nagaland on her neck. Her smile cuts distance before she does—less on the Roman sandals she wears than in the unstudied humility that frames her petite presence, long hair loose, skin glowing. Her nails wear her signature black nail polish (@gunjanwithblacknailpolish on Instagram), winks when noticed.

Annals of The Award

Last month, Gunjan Jain received the National Award for Design Excellence 2024 at a ceremony in Delhi. Her work has been profiled here before, but the award submission itself—an exacting breakdown of how Indian textiles hold both worth and endurance—repositions her as one of the country’s most significant textile practitioners.

The government’s criteria for the award are demanding: applicants must show design versatility, mastery over fibres and materials, commitment to revival, and a clear documentation of weaving techniques. “They also assess impact on grassroots livelihoods—wages, production, diversification, continuity, relevance,” she explains, her voice unhurried. She speaks of Odisha Ikat and the local fibres she has worked with since 2007 as if unveiling saris from a hanger for visitors and customers, with each drape carrying layers of stories and motifs. Fish and spices, mythical creatures and deities, flora and fauna, an inventory of life folded into textile art.

“Indian designers are spoilt for choice. For me, it’s about how open I am to change—that’s what keeps me relevant. Innovation matters, both in the product and in the storytelling,” she says.

For the award, Gunjan submitted three layered projects. The first was fibre-based: using natural materials to create ready-to-wear. She wove nettle, a medicinal plant fibre, into Ikat and tailored it into a long jacket in violet-blue, white, and black. “This is a problem–solution submission. With silk prices soaring, we must look for substitutes,” she explains. She has also been working with banana fibre and Odisha’s golden Sabai grass, long used for ropes and mats. In her hands, these rugged fibres turn supple—becoming textiles, tapestries, and wall panels that expand the vocabulary of handwoven cloth.

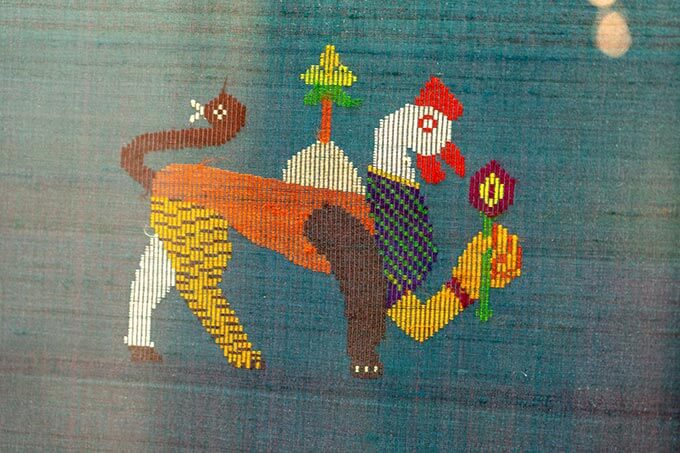

The second, and the one that brought home the award was her interpretation of Navgunjara—the mythical composite being embodying Vishnu’s nine avatars. It is part of her ongoing revival of Odisha’s temple iconography. She has carried such motifs onto saris, tapestries, and wall art. Some of these works were featured in Sutr Santati: Then. Now. Next, the exhibition curated by Lavina Baldota of the Abheraj Baldota foundation of Hospet. Mythic hybrids are a recurring tide in her practice. One of her weavers, Srikant Das, won National Merit Award for interpreting the Gaja Singha (half-elephant, half-lion) with her design.

The ‘Gaja Singha’ motif woven by an award winning weaver that works with Jain.

Seafaring and Symbolism

The third submission comes from her keen curiosity in voyages. The Bali Jaatra sari, an evolving weaving revival and innovation project which draws on Odisha’s seafaring history, commemorates the voyages to Indonesia, honouring textile connections carried across water between the two regions. Woven with three distinct Ikat techniques—including jaala weaving, which predates the jacquard—it ripples with fish, paper boats, and marine symbols. When she unfurls it, the fabric acquires a luminosity and the power of a map: trade winds, myth, symbols and marine life woven into waves. “Very little has been documented about the seafarers, about double Ikat woven in natural fibres, about textile linkages between Odisha and the village of Tenganan (in Indonesia),” she says. Gunjan refers to her physical visit to the ancient Bali Aga village in Indonesia. Tenganan’s double Ikat ‘geringsing’ cloth shares technique familiarity with Odisha’s Ikat.

Life and The Odisha Leitmotif

Born and raised in Delhi, used to the city life, Gunjan had an early warming to textile history, tradition and innovation, their conflicts and complexities as the daughter of textile historian Dr Pawan Jain. After training at the Pearl Academy in fashion design, she found herself in Odisha in 2007 and did not leave the region for a decade. “I de-schooled and then re-schooled myself,” she says. Vriksh was seeded in 2008. While she was identified early as a textile designer of worth by the Development Commissioner of Handloom and Handicrafts in Odisha, it was the cultural wrap—life, politics, society, essence and importance of the region—that guided her instinct, learning and livelihood. From the Puri temple to the state’s Pattachitra craft (also interpreted on sari pallus), she was riveted.

A soot analysis of the weaving skills and weavers in different districts brought back optimism. “Odisha’s weavers are highly skilled. They don’t need a rehaul. Just a reconstruction of the traditional motifs they work with. That’s what I do with weavers in the six clusters I work with. Challenge the shape, size and the storytelling of what has existed.”

Her universe beckons: from vegetables like bitter gourd to fish and nettle, millets to dozens of varieties of local rice (dhan), conches and marine life, Gunjan’s design map offers a reassuring sustenance. Of a life anchored in soil, sea, fibre and yarn. Mark Rothko would have paused here too, at the threshold where colour becomes emotion and cloth turns into landscape.