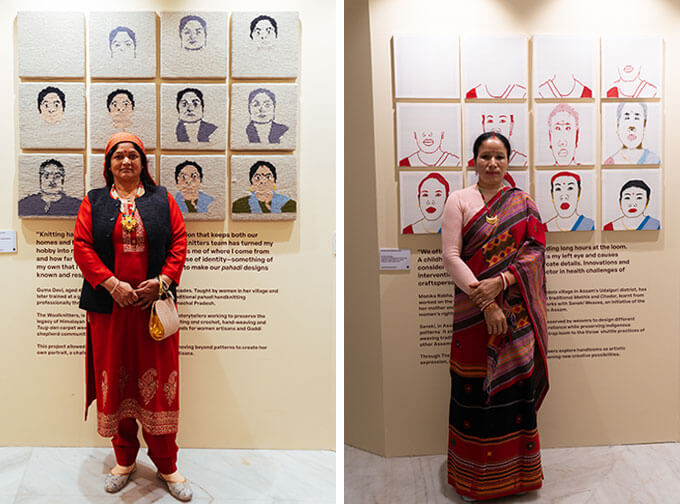

How artisans reclaimed their passport photos through weave, wool, embroidery and identity

The deeper revelation—like every monumental philosophic work teaches us, whether it is the Bible or the Rigveda—emerges only days after a seed is sown, after gestation has attached itself to evolution. The idea in question is The Right to Be Seen: Reframing the Passport Photo in Craft. On the surface, a craft project. In truth, a new way of creating content at The Voice of Fashion—one that began as a written series about reclaiming the passport photo in our cultural imagination. Commissioned to photographer-writer Nishat Fatima, it brought in some fascinating visual art projects like Samir Jodha’s work with passport identity photos of workers who built the Burj Khalifa in Dubai. And photographer Kalpesh Lathigra’s ‘The Democratic Project’, an inclusive series of photos short on the Passport Polaroid that include refugees from Sudan to Priyanka Chopra Jonas.

But as the idea, which dwelt on the biometric identity of “us”—people moving through the carousel of meaningful existence—began to take shape, we knew it could not remain confined to text. It needed to step out of arguments and acquire a life of its own.

The Royal Enfield’s second edition of Journeying Across the Himalayas (JATH), a multidisciplinary festival that “celebrates stories of and from the Himalayas,” became that womb. The metaphors I use—seed, evolution, entanglements, gestation, revelation, womb—are deliberate. They signal the poignance of birth and early life. An idea birthed in a journalistic series of stories was suddenly partnering with a festival that brings together communities, crafts, visual art, culinary traditions, music, theatre, performances and conversations. At JATH, this year’s theme was ‘Ours to Tell’. And once we understood, as a small group of content creators, that The Right to Be Seen was about bringing the faces of artisans into recognition and public attention, there was little doubt how this project should unfold.

In simpler terms: we wanted to invite artisans from clusters in the Himalayan regions, associated with the Royal Enfield Social Mission to recreate their own passport photos—their biometric identities—using the very crafts they are masters of.

Framing the Story Now in Retrospect

It is India’s first artisan-documentation project done through craft—where you don’t just see the hand-skill or the artisan’s name, but also their face. Their self-portrait. Their presence.

Now that the exhibition at Delhi’s Travancore Palace, part of the ‘Ours to Tell’ edition of JATH (4–10 December), has concluded, it is time to put the entire graph and graft of this project in perspective. The fact that Royal Enfield sensed the pulse of this untried idea and partnered with The Voice of Fashion strengthens our belief in creative risk-taking—something essential to the art-craft-journalism landscape in contemporary India.

The Right to Be Seen: Reframing the Passport Photo in Craft was conceptualised by us and curated by design curator and textiles expert Juhi Pandey. She has long experience working with craftspeople—their sensitivities, sensibilities, expectations and hesitations. She understands the art and arc of working through experimental ideas with artisans across remote regions—people who may need mentoring and nudging, yet bring their own unmistakable signature to everything they touch. Her approach was one of gentle intervention, never rearranging their fears or fascinations. We had discussed mounting the series with an Andy Warhol-ian progression—from tabula rasa to full face through several small frames. But it was Juhi’s idea to frame certain stages from the reverse side so viewers could see the stitches from the back.

No Tread, No Needle

My own revelation—after months of waking up one day with this idea—was how tiny a seed actually is. Until it is planted and nurtured by air, water, people and intent, a seed can run dry at any moment. The project may have started as a spark, but its gestation, development and realisation form the true story. Craft is organic: even when it follows a template, it improvises with emotion, history, memory, colour and the pulsations of the present—sometimes mundane, sometimes complex. No needle pierces cloth without the weight of a life lived with curiosity and perceptivity. No loom runs without the presence of mind of the weaver and the inheritance of knowledge.

We watched the seed become an embryo, then find its womb, until it was finally birthed.

Raziya Bano from Looms of Ladakh wove her self-portrait using merino and indigenous Ladakhi sheep wool. Guma Devi from The Wool knitters rendered hers with 100 per cent merino wool. Abdul Hameed Shah and the Aari embroiderers of Safa Kadal, from the Commitment to Kashmir (CToK) trust, created their images with aari embroidery on 100 per cent duck cotton cloth using cotton-polyester four-ply yarn. Monika Rabha and the weavers of Nizdola from Saneki Weaves (North East Network) used extra-weft weaving on mill-spun 2/60s cotton yarn. And Purbashri Mushahary of The Agor Weaves–ANTS recreated her passport photo on mill-spun 2/40s and 2/60s cotton yarn.

All these artisans arrived in Delhi from their Himalayan homes, and I remember bashfully asking them to pose for photographs—not just for Instagram.

Each of them had brought their own faces to life through their craft. And I must say again—this project is not about hand skill alone. It is, at its core, a visual identity project. Just the beginning. As with Royal Enfield’s Himalayan strides, we hope to give it an existence across India.